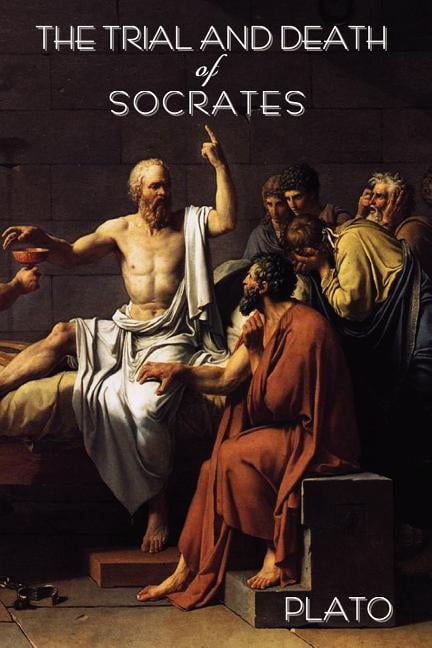

But when the ancient Athenian Socrates was delivered this news, he responded with sincere and utter disbelief – even though his friend had confirmed it with the Delphic oracle, the fortune-telling authority of the ancient world.

If your best friend told you that you were the wisest of all human beings, perhaps you would be inclined to smile in agreement and take the dear friend for a beer. We believe epistemic humility presents something of a twofold danger that makes being humble frightening – and has, ever since Socrates first put it at the heart of Western philosophy.

So why is intellectual humility in such scarce supply? Of course, the quickest answer might be the right one: that humility runs against most people’s fear of being mistaken, and the zero-sum view that being right means someone else has to be totally wrong.īut we think that the problem is more complex and perhaps more interesting. In other words, Americans have stopped listening. Perhaps this white-knuckled insistence on being right is the root cause of the societal fissure – why everything seems so irreparably wrong.Īs religion and philosophy scholars, we would argue that our apparent national impasse points to a lack of “epistemic humility,” or intellectual humility – that is, an inability to acknowledge, empathize with and ultimately compromise with opinions and perspectives different from one’s own. Critics point out endless lists of what should be fixed: the complexity of the tax code, or immigration reform, or the inefficiency of government.īut each dilemma usually comes down to polarized deadlock between two competing visions and everyone’s conviction that theirs is the right one. Kaag, The ConversationĪ common complaint in America today is that politics and even society as a whole are broken.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)